If your boss thinks you’re awesome, you will become more awesome

Ερευνα για την ευημερία των εργαζομένων

Leaders Under Pressure: Finding The Essential Skills For The New Era

If your boss thinks you’re awesome, will that make you more awesome? This question came to us recently, when we were working with the top three levels of management in a multinational. When asked to rate their direct reports on 360 evaluations, some managers consistently rated everyone higher, and others consistently lower, than the average. We wondered if this was a result of bias, and what effect it had on the people who worked for them.

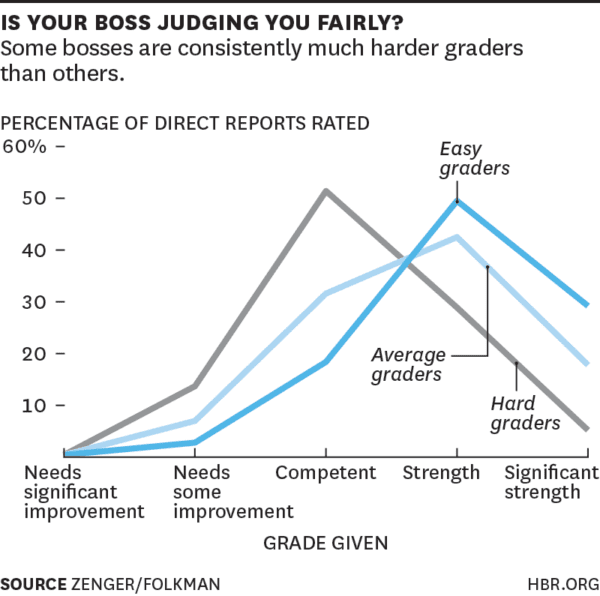

To understand this better we looked at a larger set of 360 data to identify 50 of the company’s managers who rated their direct reports significantly more positively than everyone else on a five-point scale (that is, they gave a higher percentage of their subordinates top marks than their colleagues did, skewing the curve to the right, as in Lake Woebegone, where everyone is above average). We also identified 31 managers who consistently rated their direct reports significantly lower than their colleagues, skewing their curves to the left.

The difference is stark: Only 18.4% of the people working for the “positive-rating” managers, or the easy graders, were judged as merely “competent” (that is, just average) compared with fully 51.4% of those working for the “negative-rating” managers, clearly the harder graders. While neither group judged even 1% of their workers as truly problematic and in need of significant improvement, almost 14% of those working for the negative-rating managers were judged to need some improvement compared with only 3% of those working for the positive-rating bosses.

Zenger Folkman- HBR

It’s hard to parse the meaning of these data. Are the positive-rating managers indulging in grade inflation? Do the lower ratings actually represent a more objective and deserved analysis of a subordinate’s performance? (After all, it does follow the standard bell curve.) Or perhaps the ratings are in some way self-fulfilling, and the leaders who see the best in their people actually make them better, while those who look more critically make their subordinates worse.

We favor that second interpretation since whether deserved or not, the psychological effect of these ratings was dramatic. Anyone who joined us in the discussions with the subordinates of these two sets of managers would have instantly seen the impact. The people who’d received more positive ratings felt lifted up and supported. And that vote of confidence made them more optimistic about future improvement. Conversely, subordinates rated by the consistently tougher managers were confused or discouraged—often both. They felt they were not valued or trusted, and that it was impossible to succeed.

These feelings directly translated into higher or lower levels of engagement: engagement scores for those working under the negative raters averaged in the 47th percentile, whereas scores for those reporting to the positive raters averaged in the 60th percentile. This difference is statistically significant.

It’s possible that the negative-rating managers simply had more than their share of less-engaged employees, but we believe the far more likely explanation is that everyone’s engagement levels started out roughly the same and that widely different daily interactions, culminating in extremely divergent performance reviews, had a strong impact on engagement levels.

This is a particularly alarming possibility when you consider the seemingly reasonable motives of those who gave consistently lower ratings. We frequently heard them say something like, “I want my people to get the message that I have high expectations.” Those who gave high marks to their people also had high expectations, but they were more focused on sending the message that they had confidence in their people. They truly felt that they had selected the best people for those positions, and they expected them to succeed.

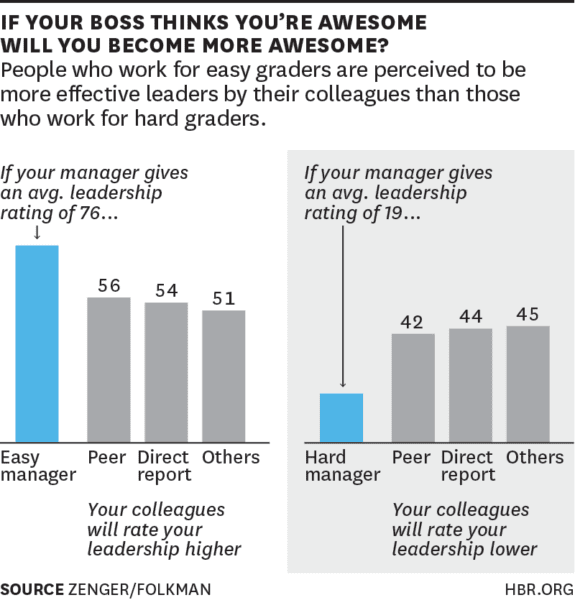

And did they? To see, we looked at the overall leadership ratings of the two groups’ 360 evaluations. We were not surprised, by now, to see that the bosses who rated everyone lower on their performance also rated them lower on their leadership abilities, while the bosses who gave the highest marks to their teams, in general, gave high marks on leadership as well. The degree of difference was startling, though—with leadership ratings averaging only in the 19th percentile for the low raters and 76% for the high raters.

And the thing is, the peers, subordinates, and other associates also rated the leadership skills of the employees working for the low-rating managers lower than those working for the high raters. The gap was not nearly as great, as you can see in the chart below, but it was consistent and significant.

The fact that the ratings given by both the low- and high-rating managers were so different from the ratings given by others suggests that both sets of managers are biased (or that managers trying to force rank their staffs are judging them unfairly). And it also shows that these biases and rankings have become self-fulfilling, influencing subordinates’ behavior to the extent that others ultimately can see it.

If this is so, these tough graders aren’t doing the organization any favors. There’s an interesting study that is related to this issue called “Predicting non-marital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis.” This was a meta-analysis of 137 studies collected over 33 years with 37,761 participants. These studies were looking at factors that cause non-married couples to break up or stay together. The number one factor that kept people together was something they called “positive illusion” – essentially that the person you’re dating thinks you’re awesome.

Is it possible, then, that if a boss thinks you’re awesome you will become more awesome? On a personal level, it’s hard to dismiss. We’ve spoken with hundreds of leaders whose bosses thought they were awesome, we know the impact is real.

Source : zengerfolkman.com